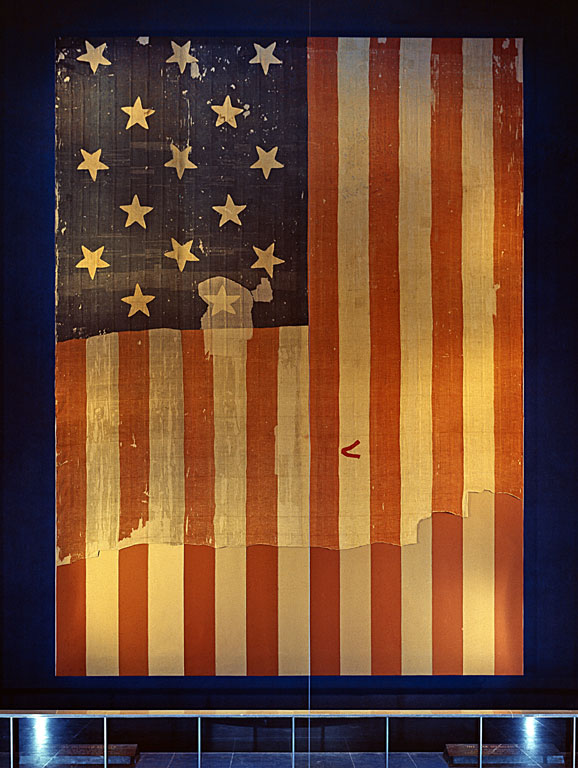

This is the original stars and stripes flag of the United States. You can see it on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. It has an interesting history. 200 years ago in July 1813, during a war between the Americans and the British, Mary Pickersgill, a hardworking widow known as one of the best flag makers in Baltimore, Maryland, received a rush order from American Major George Armistead. He had just taken over as commander of Fort McHenry and wanted an enormous banner, 30 by 42 feet, to be flown over the federal garrison guarding the entrance to Baltimore’s waterfront. I remember visiting Baltimore a few years ago and hearing the story of the star-shaped defensive fort, similar to those built by the British in Ireland such as Charles Fort in Kinsale, County Cork.

The United States had declared war in June 1812 to settle its disputed northern and western borders. During the summer of 1813, the enemies were trading blows across the Canadian border. Then British war vessels appeared in Chesapeake Bay, menacing shipping, destroying local batteries and burning buildings up and down the estuary. As Baltimore prepared for war, Armistead ordered his big new flag, one that the British would be able to see from miles away. It would signal that the fort was occupied and prepared to defend the harbour.

With her 13 year-old daughter Caroline and others, Pickersgill took more than 300 yards of English worsted wool bunting to the floor of Claggett’s brewery, the only space in her East Baltimore neighborhood large enough to accommodate the project, and set to work measuring, snipping and fitting. A rectangle of deep blue, about 16 by 21 feet, formed the flag’s upper left quarter. Sitting on the brewery floor, she stitched a number of five-pointed stars into it. Each one, fashioned from white cotton, was almost two feet across. Then she turned the flag over and snipped out blue material from the backs of the stars, tightly binding the edges; this made the stars visible from either side. (Smithsonian)

In August 1814, General Robert Ross and his seasoned troops landed near the nation’s capital. On August 24th at Bladensburg, Maryland, about 30 miles from Washington, his five-thousand-member British force defeated an American army twice its size. That same night, British troops entered Washington and set fire to the United States Capitol, the President’s Mansion, and other public buildings. With Washington in ruins, the British set their sights once again on Baltimore, then America’s third-largest city. On the morning of September 12th, General Ross’s troops landed at North Point, Maryland, and progressed towards the city. They soon encountered the American forward line, part of an extensive network of defences established around Baltimore in anticipation of the British assault.

During the skirmish with American troops, General Ross was killed by a sharpshooter. Surprised by the strength of the American defences, British forces camped on the battlefield and waited for nightfall on September 13th, planning to attempt another attack under cover of darkness. Meanwhile, Britain’s naval force was poised to strike Fort McHenry and enter Baltimore Harbor. At 6:30am on September 13th 1814, Admiral Cochrane’s ships began a 25-hour bombardment of the fort with Congreve rockets and mortar shells. After an initial exchange of fire, the British fleet withdrew to just beyond the range of Fort McHenry’s cannons and continued to bombard the American redoubts for the next 25 hours. Although up to 1,800 cannonballs were discharged at the fort, damage was light owing to recent fortification work.

At 7:30am on the morning of September 14th, Admiral Cochrane called an end to the bombardment and the British fleet withdrew. The successful defence of Baltimore marked a turning point in the War of 1812. Three months later on December 24th 1814, the Treaty of Ghent formally ended the war.

The attack on Baltimore also provided the inspiration for the American national anthem. Prior to the battle, Francis Scott Key, a Georgetown lawyer, had been negotiating for the release of an American prisoner, Dr Beanes. Boarding a British ship, Key dined with General Ross and other officers. Ross agreed to release Dr Beanes. Owing to the imminence of the British attack on Baltimore, Key was not permitted to return ashore and witnessed the massive bombardment unleashed by the Royal Navy on Fort McHenry.

The sight of the Stars and Stripes (or was it the smaller storm flag?) flying from the ramparts of Fort McHenry when the bombardment ceased is said to have inspired him to pen the lyrics of the Star Spangled Banner. These details came from the website ‘The Man who captured Washington‘ and I am grateful to John McCavitt in Belfast (@john_mccavitt) for drawing this anniversary to my attention on twitter.

Tomb of Major General Robert Ross in Old Burying Ground Halifax Photo: © courtesy of Don Sucha, Calgary

Since writing that last paragraph, my contact who introduced me to Baltimore reminds me that the corpse of Major General Ross who was killed in the Battle of Baltimore was pickled in 129 gallons of Jamaican rum. Although it was due to be returned to Ireland it was transported to Halifax in Nova Scotia, where it rests in the Anglican cemetery (see Don Sucha’s article on the Old Burying Ground).

A weekend conference is being held in Rostrevor on October 18th-20th focusing on the life and career of Major General Ross of Rostrevor, with BBC veteran Peter Snow as a key speaker. The Ross conference which is free is supported by Newry and Mourne District Council, the Ulster Scots Agency and PEACE III Southern Partnership under the ‘Future Foundations’ programme delivered by Armagh City and District Council. There is an obelisk in memory of Ross in Rostrevor.

General Ross Obelisk Rostrevor Photo: http://www.carlingfordandmourne.com