Boys work at the Artane Industrial School in Dublin, Ireland, in this undated photo contained in a report released in 2009 by the Commission to Inquire Into Child Abuse. The report stated that physical and sexual abuse occurred at the school, which was run by the Christian Brothers from 1870 to 1969. (CNS/Commission to Inquire Into Child Abuse)

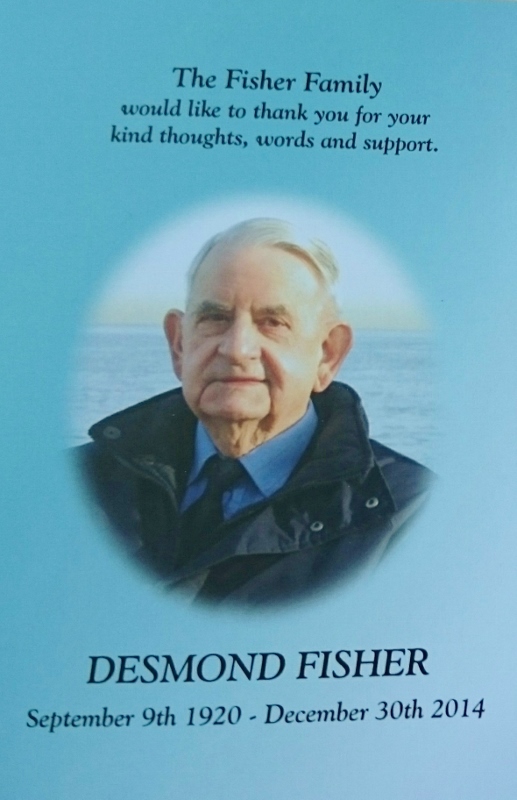

DUBLIN, IRELAND — The Irish Free State was founded in 1922. Irish journalist Desmond Fisher was then 2 years old. Now 91, Fisher, grew up with the state. A former editor of the London Catholic Herald, Fisher covered the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), later joined Radió Telefís Éireann as deputy director of news and became head of current affairs.

To Fisher, “Irish culture has always had a large complement of religion in it. Traces of Druidism and nature worship are probably still there. St. Patrick contributed the solid core. The rest is a mishmash of superstition, pietism, a sugary sentimentalism, a streak of Puritanism, and a bleak authoritarianism borrowed from Victorian England.

“It was well into the 1960s when the changes, now accelerating rapidly, in Irish culture began to manifest themselves. This was the time that Irish bishops and the whole Catholic church needed to realize that religious practice needed to change to match the cultural changes. The mistake the Irish bishops made — and are still making — is to regard theology, like the basics of the faith itself — as uniform and immutable.”

Desmond Fisher Photo: © Margie Jones

Nothing reflects Fisher’s remark on “bleak authoritarianism borrowed from Victorian England” more than the horror story that is Ireland’s “institutional abuse” in the religious congregations-run industrial training schools and reformatories for boys, and institutions and laundries for women and girls.

The 2009-released Ryan Report by the Commission to Inquire Into Child Abuse is a five-volume catalog of page after page of gross and widespread “sexual abuse” of “poorly clothed, undernourished” boys who were subject to “brutal beatings and punishments” and “poor, inadequate, overcrowded living conditions, and were “emotionally deprived and psychologically” maltreated.

Ireland’s clerical sexual file begins with a suit against the Ferns diocese and the papal nuncio (he claimed diplomatic immunity) by Colm O’Gorman, sexually abused as an adolescent in the Ferns diocese in County Wexford. O’Gorman, later an Irish senator, now Amnesty International Ireland president, was awarded some $450,000 damages. He founded an abuse-victim advocacy group, One in Four, in England and Ireland, and his subsequent BBC documentary “Suing the Pope,” helped his campaign for a Ferns diocesan investigation. The report finally disclosed more than 100 allegations of abuse against 21 Ferns priests. His BBC documentary, “Sex Crimes and the Vatican,” aired in 2006.

“We in Ireland now are struggling with ways to have the kind of public conversation we needed to have at the time of the foundation of the state,” O’Gorman said. “If you look at some of the principles that underpinned the notion of what this republic might be, its first duty (incorporated into the 1937 Irish Constitution) is to safeguard its children. But can you have a common morality if that morality is dogmatically enforced, rather than considered and engaged with and developed? Without these steps we cannot have a mature society, and we don’t have one. Yet.”

After Ferns (2008), came reports on the Dublin archdiocese (2009), and the Cloyne diocese (2011) — the latter triggered Taoiseach Enda Kenny’s attack on the Vatican. The same litany of sexual abuse in Ireland is familiar to all countries dealing with it: denial and cover-up, and hovering over all, papal, Vatican and local hierarchical obfuscation or worse. Due next: a report on the Raphoe diocese in Donegal.

Next is the unresolved Magdalene laundries abuse. The account of decades-long institutional incarceration of women in these laundries sears the soul: Women slaved away, unpaid, bullied, often underfed, and basically unappreciated. This because they had children out of wedlock, or were prostitutes, or girl children considered “at risk” — their families couldn’t control them or didn’t want them — and first offenders were sent to laundries rather than reformatories. Many lived and died there in these institutions, unmourned, relatives never notified, buried in unmarked graves.

A subtext to the laundries’ shame is the suppression of women’s rights in Ireland. Contraceptive use was a criminal offense from 1935 until 1985. Women could not collect their own children’s state allowance until 1974, their husbands did; nor could women sit on juries until 1976. Divorce was constitutionally prohibited until 1995, five years after marital rape was criminalized. If women’s rights were delayed, adoptees’ rights were nonexistent. Adoption was secret; babies were secretly sent to the United States. Files remain closed.

In the past eight years, as the group Justice for Magdalenes stepped up its pressure on religious congregations and the Irish government for apologies and restitution for Magdalene victims, the organization has made adoptees’ rights a companion issue to laundries’ redress. Magdalene laundries exposés in books, television programs, newspaper investigations and Peter Mullan’s 2002 movie, “The Magdalene Sisters,” keep the topic before the public.

Finally, in 2009, a parliamentary all-party investigation into the Magdalene laundries was announced. Its report is pending. The Conference of Religious of Ireland, an association of 136 religious orders of men and women, this year stated on behalf of the four congregations who operated Magdalene laundries (Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, Religious Sisters of Charity, Sisters of Mercy and the Good Shepherd Sisters), “As the religious congregations, who, in good faith, took over and ran 10 Magdalene homes during part or most of that time, and as congregations still in relationship with many residents and former residents, we are willing to participate in any inquiry that will bring greater clarity, understanding, healing and justice in the interests of all the women involved.”

No governmental or congregational redress, compensation or apology has yet been made, said Justice for Magdalenes.

In a statement to NCR, Mercy Sr. Coirle McCarthy, her order’s congregational leader, said, “The sisters believe they have been misrepresented and demonized in recent years and portrayed in a way that seeks to undermine their voluntary service.”

To further the sisters’ earlier offer contribute to an independent fund for Magdalene survivors, the Mercy Sisters have requested a meeting with Education Minister Ruairi Quinn, she said. (Quinn’s office confirmed to NCR he would meet with them.) McCarthy said their 2009 offer includes (in approximate U.S. dollars) $27 million to an independent fund and properties valued at $15 million. Properties worth a further $110 million have been offered to the state, and $20 million in property offered to the voluntary sector.

“In the last 10 years alone,” she said, “the sisters have [also] donated cash and property in excess of $1.4 billion to ensure [their other] voluntary services continue for present and future generations.”

If, as Fisher said, the bishops continue to regard theology as “uniform and immutable,” what then? Mary Condren of the Dublin-based Institute for Feminism and Religion contends Ireland will retain “the same scapegoat theology that brought us 35 years of terror, clerical abuse and the Magdalene laundries.” Even worse, she said, such a theology “is likely to be reinvigorated with the forthcoming centenary celebrations of the Irish 1916 Easter Rising, at a time when what’s still needed is a theology of mercy, not sacrifice.”

What is also needed is latitude for theologians to deal with the issues of the time, whether in the church, in Ireland, or in the broader West with its rising evangelical fundamentalism and atheism. According to Dominican Sr. Margaret MacCurtain, for centuries it was the religious orders that provided the men and women “with the intellectual and spiritual energy” to meet society’s and the church’s contemporary major challenges.

The major losses in vocations to the religious orders, then, remain one problem, Rome’s penchant for silencing dialogue and debate, the other.