Major Willie Redmond of the Royal Irish Regiment was killed on the first day of the Battle of Messiness on 7th June 1917. He is buried at Locre (Loker) but in a separate grave alongside the British military cemetery at Locre Hospice.

The grave is marked by a stone cross, paid for by his family from Wexford. Someone has left a Wexford flag at the foot of the memorial as a reminder of the county of his birth.

Beside the grave there is a wooden structure containing a statue of Our Lady and a repository where the visitors’ book is kept.

Locre Hospice Cemetery(CWGC) is beside the site where Major Redmond is buried

The following details about Major Redmond are taken from an article in Irish Legal News 05/04/19 by Seosamh Gráinséir:

“A famous Irish nationalist, William Hoey Kearney Redmond came from a (Catholic gentry) family of parliamentarians. His father, William Archer Redmond, was a Member of Parliament in Westminster for the Home Rule Party. His older brother, John Edward Redmond, was a Member of Parliament and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

On 24th March 1884, Willie himself was sworn in as a new MP for his father’s old constituency, Wexford Borough, at the age of twenty-two. During his thirty-three years as an MP, Willie went on to represent Fermanagh North for seven years after the Wexford Borough constituency was abolished, and then East Clare for 25 years. Willie was succeeded in that constituency by Éamon de Valera, who won the by-election triggered by Willie’s death.

Like his father and brother, Willie was a passionate supporter of Home Rule, which he said was necessary because the Union “has depopulated our country, has fostered sectarian strife, has destroyed our industries and ruined our liberties”. An ardent opponent to landlords, Willie had been imprisoned a number of times for his work with the Land League agitation (Denman 1995).

Having served with the Royal Irish Regiment for a couple of years after finishing school, Willie was described as having always been a “soldier at heart”, the “spirit of comradeship and discipline” having appealed to him. When the Great War broke out in August 1914, he had already been involved with the Irish Volunteers. But he believed that if Germany won the war, Ireland was endangered too. Intent on joining the Royal Irish Regiment again and troubled by the idea of recruiting for the war effort without joining the fight himself, he wrote: “I can’t stand asking fellows to go and not offer myself”.

In this vein, Willie told the Irish Volunteers assembled outside the Imperial Hotel in Cork in November 1914: ‘I speak as a man who bears the name of a relation who was hanged in Wexford in ‘98 – William Kearney. I speak as a man with all the poor ability at his command has fought the battle for self-government for Ireland. Since the time – now thirty-two years ago – when I lay in Kilmainham Prison with Parnell. No man who is honest can doubt the single-minded desire of myself and men like me to do what is right for Ireland. And when it comes to the question – as it may come – of asking young Irishmen to go abroad and fight this battle, when I am personally convinced that the battle of Ireland is to be fought where many Irishmen now are – in Flanders and France – old as I am, and grey as are my hairs, I will say: ‘Don’t go, but come with me!’”

(Terence Denman, A Lonely Grave: The Life and Death of William Redmond, Irish Academic Press 1995).

House of Commons WWI Memorial with name of Major W. Redmond MP

Redmond is commemorated on Panel 8 of the Parliamentary War Memorial in Westminster Hall, one of 22 MPs who died during World War I to be named there. He is one of 19 MPs who fell in the war who are commemorated by heraldic shields in the Commons Chamber. A further act of commemoration came with the unveiling in 1932 of a manuscript-style illuminated book of remembrance for the House of Commons, which includes a short biographical account of the life and death of Redmond.

The people of Loker continue to attend to his symbolic grave with great respect, organising Commemorations, the last in 1967 (organised by a Catholic priest Father Debevere) and in 1997 (organised by Erwin Ureel), refusing to allow the grave to be moved. Redmond’s Bar, an Irish pub in nearby Loker, is named after him. I enjoyed a nice bottle of local Belgian beer (Hommelbier from Poperinge) that went down well with a mackerel salad and chips.

In Wexford town there is a bust of him by Oliver Sheppard in Redmond Park which was formally opened as a memorial to him in 1931 in the presence of a large crowd including many of his old friends and comrades and political representatives from all parts of Ireland. It was re-launched by the Wexford Borough Council in 2002.

An official wreath laying ceremony took place at Redmond’s grave on 19th December 2013, when the Taoiseach Enda Kenny TD and British Prime Minister David Cameron MP paid tribute to him. Enda Kenny reflected: “The thought crossed my mind standing at the grave of Willie Redmond, that was why we have a European Union and why I’m attending a European Council” (Lise Hand, The Irish Independent 19/12/2013).

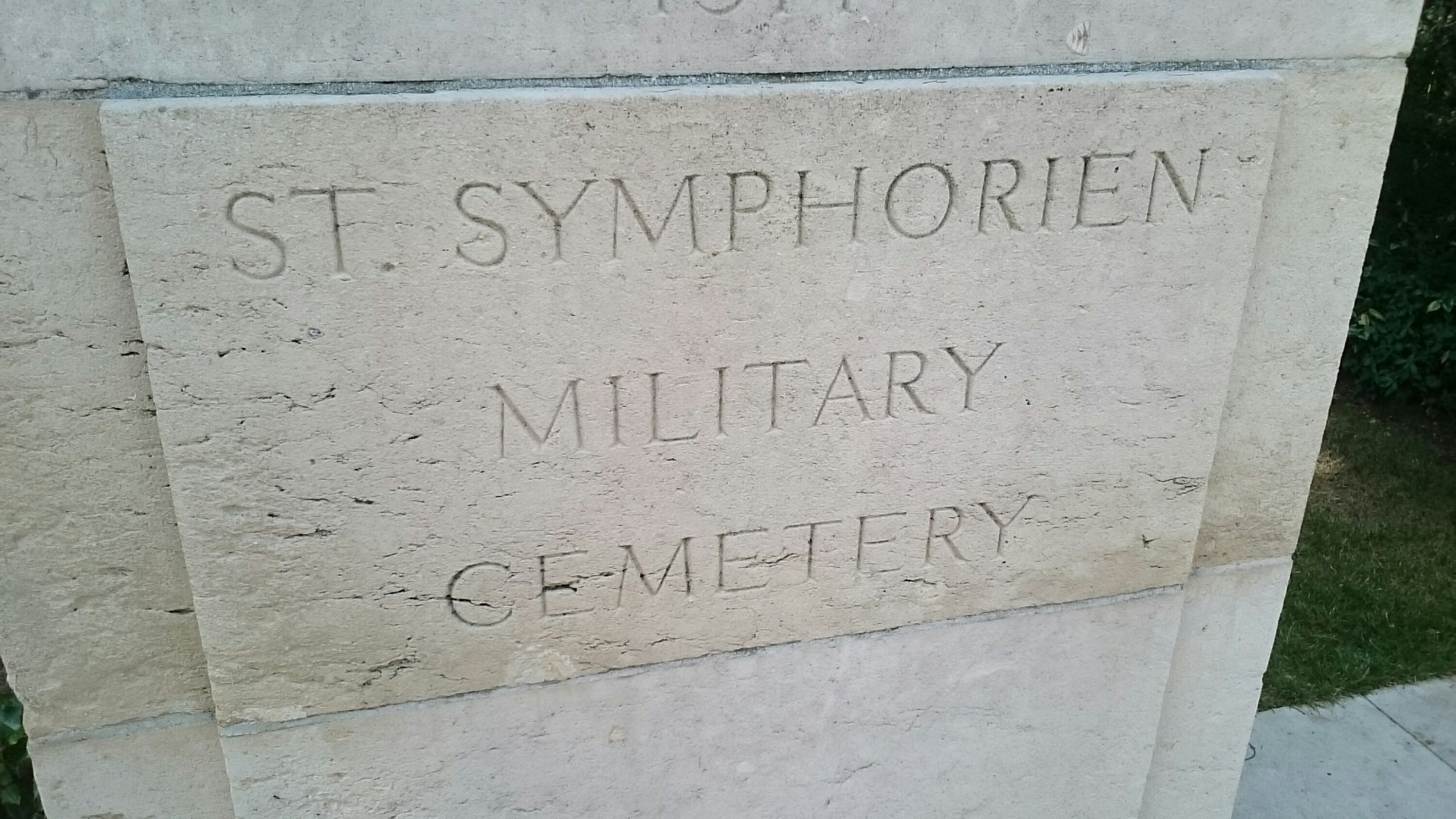

St Symphorien Cemetery is 2km east of Mons in Belgium and is maintained by the

St Symphorien Cemetery is 2km east of Mons in Belgium and is maintained by the