Plaque outside Church

Close-up of Plaque

Plaque Inside Church

VCs Information Plaque

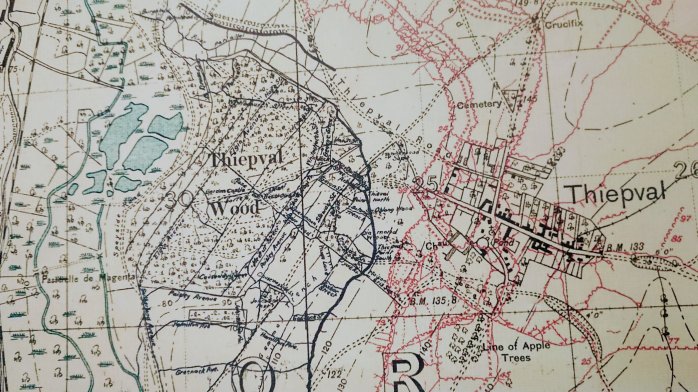

Private Thomas Hughes of the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers was born in Corravoo, Castleblayney, in 1885. He was 29 when the Great War began. He was awarded the V.C. for actions at Guillemont in France during the Battle of the Somme on 3rd September 1916. Plaques at the Catholic church in Guillemont commemorate him and two other holders of the Victoria Cross. Our group visited the church on the third day of our visit to World War One sites.

The citation read: “For most conspicuous bravery and determination. He was wounded in an attack but returned at once to the firing line after having his wounds dressed. Later seeing a hostile machine gun, he dashed out in front of his company, shot the gunner and single handedly captured the gun. Though again wounded, he brought back three prisoners”.

King George V presents Pte Hughes with his VC in Hyde Park in 1917

Walking with the aid of crutches, Hughes was personally awarded the Victoria Cross by King George V at an investiture at Hyde Park in London on 2nd June 1917. He also received the 1914–15 Star, British War Medal and Allied Victory Medal. Hughes was later promoted to the rank of Corporal. It was his custom each year to attend the Armistice Day ceremony at the Cenotaph in London. When he returned to Ireland, it was a very different country to the one he had left. Soldiers who had gone to fight in the British cause were often shunned and their exploits were largely forgotten.

Thomas Hughes died on 8th January 1942, aged 56, and is buried in the cemetery at St Patrick’s Church, Broomfield. His Victoria Cross medal is held by the National Army Museum, Chelsea in London.

Grave of Pte Hughes in Broomfield, Co. Monaghan Pic. Monaghan Heritage

Speaking at the unveiling of a blue plaque memorial for Pte Hughes in Castleblayney in February 2017, Minister Heather Humphreys said she had travelled to Thiepval and Guillemont in July and September in 2016, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, and to remember the many Irish men who died there from the 36th Ulster Division and the 16th Irish Division. In the small, beautiful church in Guillemont, a tiny village in Northern France, she saw the plaques on the wall in honour of Thomas Hughes.

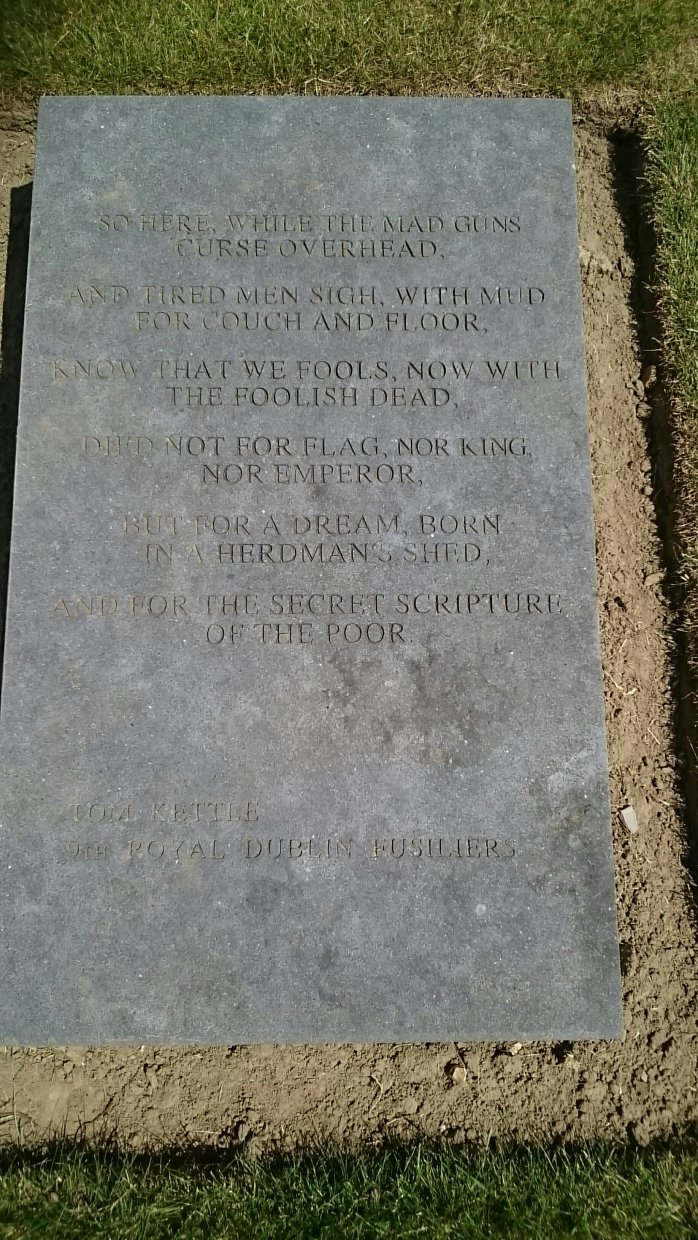

Hughes is one of 27 Irish holders of the Victoria Cross for whom the British government arranged a paving stone to be placed at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, paid for by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Stone for Pte Hughes VC unveiled at Glasnevin

Despite the romance sometimes portrayed in newspaper columns such as the Northern Standard, recruitment to the British Army remained very low for the county for the entire war. By October 1916 only 738 men from County Monaghan had answered the call to enlist, the majority being Protestants (although they represented approximately one-fifth of the population at the time). Slow recruitment was blamed several times on the prominence of agriculture in the county, with the farming classes accused of not wanting to go to war because they were prospering financially.

In total around 2,500 Monaghan men served in the Great War. There were notable contributions from some families. Seven Roberts brothers from Killybreen in Errigal Truagh all joined the British army at different stages. Seven sons of Sir Thomas Crawford of Newbliss served, and three of these were decorated for gallantry. Four Steenson brothers from Glaslough joined up and two were killed. In all, nearly 540 Monaghan men were killed in the war, about half of them Protestant and half Catholic.

Blue plaque in Castleblayney for Private Thomas Hughes VC

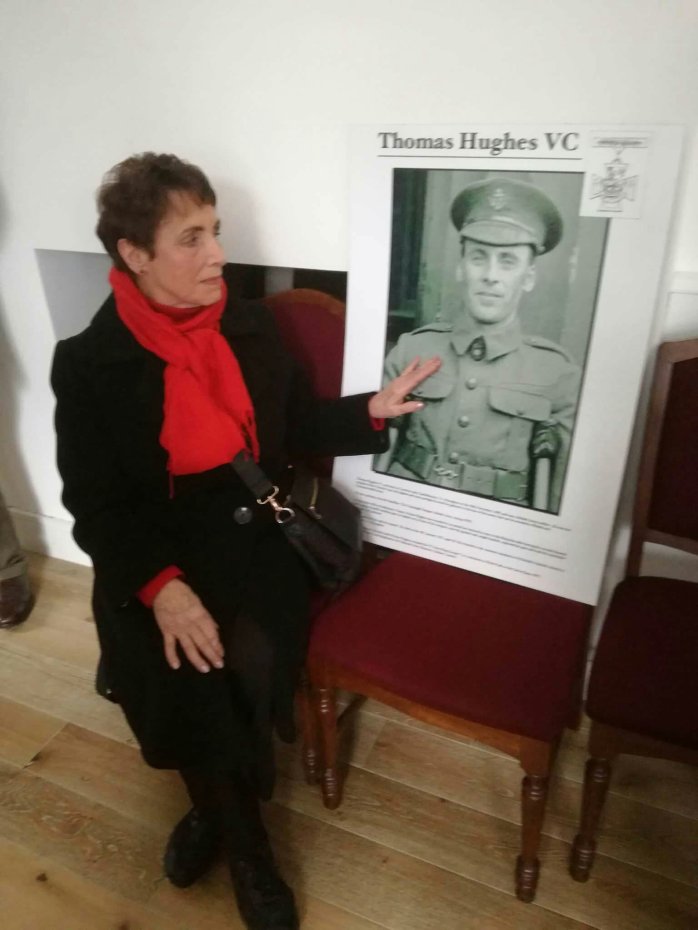

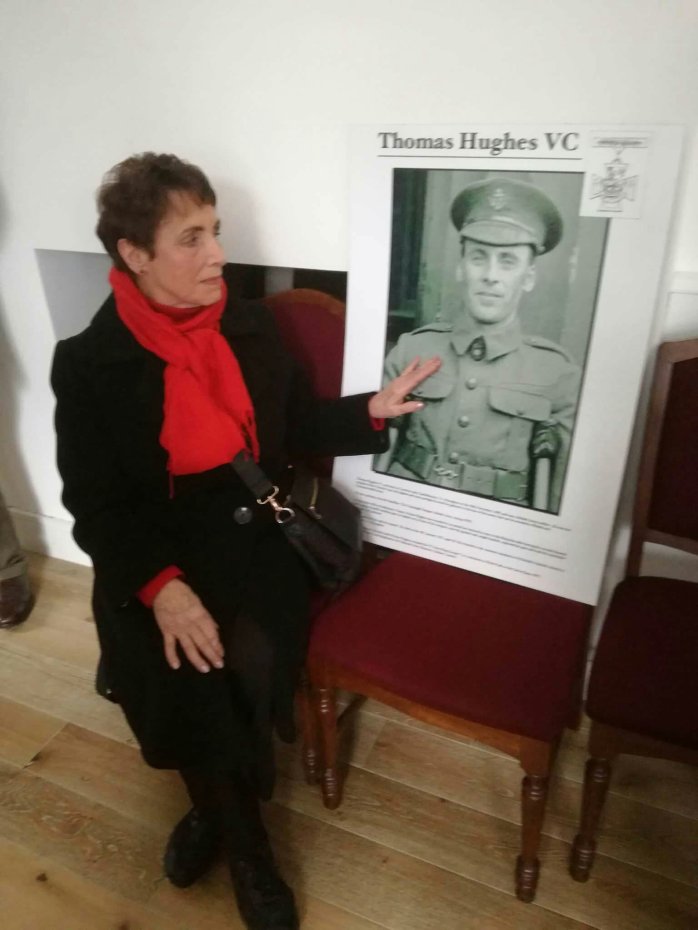

The unveiling of the Ulster History Circle blue plaque for Private Hughes in Castleblayney was attended by his niece Josephine (Hughes) Sharkey from Dundalk, and her daughter Siobhan. Other relatives included PJ McDonnell, (originally from Broomfield), Chair of the Monaghan Association in Dublin. His father’s mother and the mother of Thomas Hughes were sisters. Other relations came from the Donaghmoyne area, including Ann Christy, a grand niece, Brian Conway from Castleblayney, Pauline McGeough (Broomfield), Rosemary Hughes-Merry (Castleblayney), Angela McBride from Carrickmacross and a distant cousin, Frank Hughes, originally from Laragh.

Niece of Pte Hughes, Josephine Sharkey from Dundalk, with his portrait

The attendance included former members of the Irish Defence Forces from the Blayney Sluagh group, representatives of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and the regimental museum in Enniskillen, members of the Lisbellaw and south Fermanagh WW1 Society (who also visited the grave of Private Hughes), and the curator of Monaghan County Museum, Liam Bradley, who had organised a number of events for the 1916 Somme centenary.

Siobhan (Hughes) Sharkey read a poem which had been specially composed for the occasion of the presentation of the Victoria Cross to Private Hughes in 1917. On his return to Castleblayney, the urban district council with Lord Francis Hope arranged an address of welcome for Hughes to celebrate his bravery on winning the “coveted trophy which is emblematical of the highest bravery on the battlefield”. Local dispensary Dr J.P. Clarke said it was with great pleasure he read in the press of the coveted decoration “being pinned to the breast of our hero.” He did not know whether it was time for poetry or not, but anyhow he could recite them a few lines he had composed for the occasion (in Castleblayney in 1917)…

POEM: THOMAS HUGHES V.C.

“Before the Kaiser’s war began with frightfulness untold,

How many a peaceful hero worked in many a peaceful fold,

How many a valiant soldier strove to keep the home fires bright,

How saddened skies weep over their graves in pity through the night.

From Suvla Bay to doomed Ostend, from Jutland to Bordeaux,

They fought and bled and died to save these countries from the foe;

In Flanders, France and Belgium, from Seine to Grecian shore,

Brave were the deeds and bright the hopes of boys we’ll see no more.

‘Mongst them times forty thousand men picked out from Ireland’s sons,

Who went to fight the Austrians, the Bulgars, Turks and Huns,

How few returned with due reward their valour to repay,

But Thomas Hughes of Corravoo, V.C., is here to-day.

A Blayney man whose noble deeds uphold our country’s pride,

Who saved his comrades, took the gun, cast thought of self aside,

And changed defeat to victory in blood-soaked trenches when,

He ranked with bravest of the brave — the Connaught Rangers men.

Tom Hughes was reared where sun at dawn makes shadows lightly fall,

Across Fincarn’s ancient hill so sacred to us all;

For there tradition tells an Irish hero proudly rests,

Strong Finn McCool, the warrior, enshrined in Irish breasts,

Near by the road in Lackafin, beside lone Corravoo,

Remains of Irish chiefs are found in cromlech plain to view,

Among these scenes his youth was passed, no recreant was he,

For when his chance to fight arrived he well won his V.C.

He faced grim death while all around like Autumn leaves men fell,

He fought good fight and gained the day despite the raging hell

Of bullets, bayonets, shrapnel, Jack Johnson’s gas set free.

Now raise three cheers, and three times three, for Thomas Hughes V.C.!”

Unveiling of plaque in Castleblayney by Minister Heather Humphreys TD (right) and relatives of Pte Hughes VC